April 2024: what the hell is a body without organs anyway?

Trying to figure out what Deleuze and Guattari were on about

I’ve been vaguely thinking of reading some Deleuze for a while now. I’ve got a surprising amount out of reading Derrida, and I know Deleuze also has some ideas about difference that maybe contrast in interesting ways.

I’m not sure this is the best route in, but I like the idea of investigating the mysterious phrase “the body without organs”, inspired by these notes by Mike Travers and the EXPLAIN DELEUZE TO ME OR I'LL FUCKING KILL YOU! copypasta. This is going to be similar to the speedrun format I’ve used before, where I set a one hour timer and try and find out what I can about a subject, but with more of a leisurely pace. I’ll spend a few hours reading and writing, and clean it up a bit afterwards so that it’s hopefully not too painful to read.

I know so little about this subject that I’m also pretty lost on the meta-level of knowing what sources will be any good, and I might choose badly. And beyond that, I don’t have much sense of whether I’ll even find this concept useful, rather than just bogus or too vague to be useful. So it’s going to be a journey through fog. Let’s see what happens.

Eggs

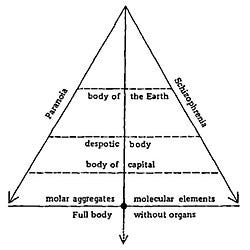

As with all my speedrun posts I’m going to start by poking around the Wikipedia article to try and get oriented. There’s a helpful diagram at the start:

I mean, that’s cleared it all up, right? I hardly need to bother with the rest of this post.

I guess I could still be missing some of the finer points, though, so let’s continue. There’s also an example. Which turns out to be brilliantly concrete and literal – an egg is a body without organs!

In this case we’re talking about an egg that’s been fertilised, so that it’s in the process of becoming a body, but that’s still at the stage where it’s full of poorly differentiated liquid gloop rather than distinct organs:

As a bird egg develops, it is nothing but the dispersion of protein gradients, which have varying intensities and have no apparent structure; for Deleuze and Guattari, a bird egg is an instance of life "before the formation of the strata", since changes in the qualitative elements of the egg will emerge as a changed organism.

So, OK, that is a lot more straightforward than anything I could have hoped for, but what exactly is it supposed to be illustrative of?

The concept describes the unregulated potential of a body — not necessarily human— without organizational structures imposed on its constituent parts, operating freely.

I think the idea of the egg is that it’s some kind of freeform potential that hasn’t yet been locked into a particular top-down design. Why we want a concept for this will hopefully become clearer later. I’ll get back to that when I read something in more depth, but let’s finish off the orientation part by checking when and where the term comes from:

The term was first used by French writer Antonin Artaud in his 1947 play To Have Done With the Judgment of God, later adapted by Deleuze in his book The Logic of Sense, and ambiguously expanded upon by himself and Guattari in both volumes of their work Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

The Wikipedia article only has a small fragment of Artaud’s text, so I looked up the context and it’s pretty striking:

Man is sick because he is badly constructed.

We must make up our minds to strip him bare in order to scrape off that animalcule that itches him mortally, god, and with god his organs.For you can tie me up if you wish,

but there is nothing more useless than an organ.When you will have made him a body without organs,

then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions

and restored him to his true freedom.

It’s also probably significant that Artaud was institutionalised for large parts of his life, and was writing this from inside a psychiatric hospital.

Machines

Next, I want to read something more substantial. I’m going to go with What is the body without organs? Machine and organism in Deleuze and Guattari by Daniel Smith, which I found by typing “body without organs” into Google Scholar and picking the most lucid result on the first page.

This paper situates the body without organs in the context of an older philosophical debate on the differences between machines and organisms. Machines were classically thought to be predictable and have fixed functions, whereas organisms act in more spontaneous, open-ended ways.

(Sidenote: what kinds of machines are we even talking about here? One section of the paper deals with Samuel Butler talking about “vapour engines”, so Industrial Revolution stuff. But we’re also going back as far as Descartes thinking about clocks and artificial fountains. I guess this all forms a reasonably distinct category of human-made objects with autonomous, rigid movements.)

Deleuze and Guattari are going to muddle this distinction by bringing out the opposite qualities:

If classical vitalism contrasted the ‘‘good’’ creative, spontaneous organism to the ‘‘bad’’ inert, lifeless machine, Deleuze and Guattari will emphasize, on the contrary, the ability of the machine to create something new, and also the normalizing and constraining aspects of the organism.

The paper discusses several examples of “organism-like” features in machines. I’m going to focus on unpredictability because it gets into some ideas about difference that I already wanted to use as an entry point into Deleuze’s writing. In Difference and Repetition Deleuze is apparently interested in the way that repetitions can introduce difference into the thing they repeat. Smith gives the example of musical performances:

Consider, for example, the various performances of a piece of music, each of which constitutes a ‘‘repetition’’ of the notation written out by the composer. In each performance, the same thing is repeated (the written score), but the work that is produced can vary enormously, whether because it is played by different musicians, conceived by a different conductor or musical director, or even played differently by the same musicians on different nights.

Now classically we don’t think of machines as having this sort of “productive difference”. The prototypical machine is thought of as doing the same repetitive thing over and over.

Deleuze and Guattari instead highlight the fact that a given machine can be put in many different contexts. Maybe it was designed to do a particular thing, but in practice it can be put in a different situation, or in combination with a bunch of other machines, and that environment will modify the effect of the repetition and produce interesting differences.

(This has some similarities with Derrida talking about iterability – a given piece of text can be reused in very different contexts. Anything that was irretrievably tied to a single context would be too inflexible to count as text, it would be something like a inarticulate cry or gesture.)

That’s the machines-as-creative part of the story. Then there’s the organisms-as-rigid part. This is where Deleuze and Guattari’s specific definitions of “organs” and “organisms” come in:

The word organism, rather, describes a type of body that is organized in a certain way, namely one that is ‘‘centralized,’’ ‘‘hierarchized,’’ and ‘‘self-directed.’’ The ‘‘organs,’’ as we have already seen, are understood by Deleuze and Guattari on the model of the machine, and the organism is the higher-order construction which holds the organs together, giving them a unified, regularized form (they twice use the phrase ‘‘the organization of organs we call the organism’’).

So the organs are kind of free little machines, and the organism constrains them and subordinates them to a plan. One example they give is the homologous bone structures of vertebrate arms, with the same “organs” being used as arms, flippers or wings in humans, whales and birds.

OK, so what does all this have to do with the body without organs? Well, the term is kind of backwards, and it’s more like the organs without the body:

As scholars have noted, the body without organs (sometimes abbreviated to BwO) is a somewhat confusing term, because it does not describe ‘‘a body deprived of organs,’’ as the term seems to indicate, but rather ‘‘an assemblage of organs freed from the supposedly ‘natural’ or ‘instinctual’ organization that makes it an organism.’’

So the organs are like productive little machines that are freed from their standard context to do different things.

There’s one example, now, to do with the human face:

It is clear that the face is not wholly subordinated to organic functions: we use it to express our emotions, we treat it as an aesthetic object, we use it for communication, and so on. In fact, if one believes the early Levinas, the human face opens us to the very possibility of ethics. All of these functions have nothing to do with the head qua organism, and would not have been made possible had the face not first been ‘‘freed’’ from its relation with the organic body and its place within this hierarchy of its system.

I would like more examples. Maybe I have to read A Thousand Plateaus. But this is as far as I’ve got with reading for now.

Some final thoughts

The Smith paper did turn out to be very lucid, way clearer than I expected. I suspect that it’s actually a bit too lucid, in that it just picks one unusually coherent route through the material and ignores the rest. There are plenty of mysteries left. What’s the link to capitalism and schizophrenia? What’s that weird diagram about?

I’m completely happy with that outcome, though. The Smith paper gives me something that’s clear and concrete enough to be a place to start. I can always blur and complicate that later, but it’s nice to have some reasonably stable ground to start from.

My current feeling is that there’s something to this idea of the body without organs that would be worth investigating further. I’m not very excited by it yet, but also I don’t think it’s completely bogus or useless. Here’s one short attempt to use it for myself.

A while back I was reading Vygotsky’s Thought and Language, on how children learn to form concepts, and what they’re really learning when they learn new words. To quote from that newsletter:

[Vygotsky] points out that most words that children learn are already in use by adults, so their meaning has been stabilised. So young children learn to say ‘cat’ when an adult says ‘cat’, but that doesn’t mean that they are extending the concept in exactly the same way.

The adult understanding of “cat” has been socially stabilised, and in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms is something like an organ subordinated to the structure of the whole organism of language. Vygotsky wanted to see what the individual organs did, so he studied how children learn artificial concepts, which weren’t constrained by the body of language and could act individually as free little text machines.

Is this a useful way of thinking about what Vygotsky did? I don’t know. But it’s nice to feel like I can think with this weird body-without-organs concept at all.

Next month

I just started skimming the early part of A Thousand Plateaus and it’s… semi-readable. Could be worse. Better than Derrida. So I might read some more.

Or I might not. Why do I even include this section.

Cover illustration of eggs is from here.

I suggest "What is Philosophy?" as their most clearest and also imo best work, there's an essay I wrote on their understanding of science I can link

I guess if you really must read Anti-Oedipus...

You could take a look at what they mean by "desiring machines".

And, if I recall correctly, they raise a question: whose fantasy is the Oedipus complex anyway? That is, with which character are people identifying to make the trope popular?