August 2020: The Roots of Romanticism

Isaiah Berlin on Hamann, Herder, Kant, and the early days of the romantic movement

Hello again! I'm remembering why this newsletter thing works so well for me now, and why my writing output crashed as soon as I dropped it. The key thing about it is that I know I have a deadline at the end of the month, and so during the month I have a sort of background loop in my mind that's trying to figure out what to say and how to structure it, which forces to me to articulate my ideas more carefully. I didn't start writing this until the last weekend of August, but because I'd already been doing all this background thinking I mostly had to just get it on to the page. It's still quite a time commitment to do a good one, so I probably do have to drop it or phone it in when things get busy, but it pays off so well that I should at least try.

(I think this also points to why the daily notebook idea didn't quite work for me. A month feels like about the right timescale for this sort of background loop. I could maybe do something on the scale of a week, but a day is just way too short to digest much, and the results felt very thin and unsatisfying.)

This one is mostly going to be about Isaiah Berlin's The Roots of Romanticism. I'm only halfway through this, but there's already so much to say about it that it takes up a newsletter's worth on its own. Almost, anyway. After I thought I was finished I remembered a second reason I like the newsletter format, so there's a short section on that at the end.

In the last newsletter I claimed I was going to talk about physics in August, either here or on the blog, and that hasn't happened. I did actually make decent progress on a post on Bell's theorem, and hopefully I will finish it soon, but working this year is like pushing through a wall of sludge and everything takes forever. Plus it genuinely is quite a complicated fiddly post.

I did get out one blog post, another speedrun, this time on a bunch of Russian psychologists. Vygotsky, Luria and some others. I was hoping for an interesting story about something called the Vygotsky Circle, but actually it was a confusing mess and not very enlightening. Some good followup on Twitter though.

So... on to the Berlin book. I think I first saw it mentioned in Iain McGilchrist's The Master and his Emissary, which is partly a fascinating book about brain hemisphere differences and partly a giant sprawling attempt to apply the hemisphere idea to all kinds of movements in Western art, philosophy and society. I'm really not sure what I think about this book and I'm still trying to sort that out. My lazy argument against it is 'this is just warmed-up romanticism with some brain stuff added', but it's a bit stupid me saying this when I know so little about romanticism. So I want to learn more.

The book was originally a series of lectures, given to an audience in Washington in 1965 and broadcast to BBC radio. It's not just a transcription, it's been cleaned up to be more 'text-like', but still has an enjoyably conversational feel.

I've got a couple of reservations about this book which I want to flag before I start. The first is to do with the style. Berlin has this witty, urbane midcentury style which I love – I could read piles of this stuff. It's not a romantic style at all... it's not dry or technical either, there's a bit of warmth to it, but it's very controlled, there’s a bit of ironic distance, none of the GIANT OUTPOURING OF EMOTION I associate with romanticism. Tbh I'm much more comfortable with this – I don't quite get romanticism deep down – but it still makes me suspicious that someone who writes in this style is also going to not quite get it, and miss some of the point. Still, I'm actually willing to read this, and I probably would not read a whole load of romantic rhapsodising.

The second reservation is that I have no idea how true any of this is! These are popular talks, and Berlin hardly quotes any primary sources at all, and I certainly haven't gone and looked any up. He's an entertaining speaker, but it's all a little bit too fluent, and I'm suspicious that the entertainment comes at the expense of getting the details right. So I'm treating this book as something that gives me a vague idea of the characters involved and some of the spirit of the time, and that can point me towards other sources if I get interested. Sort of like Bertrand Russell's western philosophy book, or E.T. Bell's Men of Mathematics.

OK, so now I'm going to quote a big chunk from the book. As a warning, I’m going to quote lots of big chunks in this newsletter. I normally do that a lot anyway because I’m too lazy to summarise, but I enjoy Berlin’s style so much that I don’t want to cut him off, and the temptation’s even stronger than normal. Anyway this quote gives a good idea of that style, and also introduces the central question:

Suppose you were travelling about Western Europe, say in the 1820s, and suppose you spoke, in France, to the avant-garde young men who were friends of Victor Hugo, Hugolâtres. Suppose you went to Germany and spoke there to the people who had once been visited by Madame de Staël, who had interpreted the German soul to the French. Suppose you had met the Schlegel brothers, who were great theorists of romanticism, or one or two of the friends of Goethe in Weimar, such as the fabulist and poet Tieck, or other persons connected with the romantic movement, and their followers in the universities, students, young men, painters, sculptors, who were deeply influenced by the work of these poets, these dramatists, these critics. Suppose you had spoken in England to someone who had been influenced by, say, Coleridge, or above all by Byron – anyone influenced by Byron, whether in England or France or Italy, or beyond the Rhine, or beyond the Elbe. Suppose you had spoken to these persons. You would have found that their ideal of life was approximately of the following kind. The values to which they attached the highest importance were such values as integrity, sincerity, readiness to sacrifice one’s life to some inner light, dedication to some ideal for which it is worth sacrificing all that one is, for which it is worth both living and dying. You would have found that they were not primarily interested in knowledge, or in the advance of science, not interested in political power, not interested in happiness, not interested, above all, in adjustment to life, in finding your place in society, in living at peace with your government, even in loyalty to your king, or to your republic. You would have found that common sense, moderation, was very far from their thoughts. You would have found that they believed in the necessity of fighting for your beliefs to the last breath in your body, and you would have found that they believed in the value of martyrdom as such, no matter what the martyrdom was martyrdom for. You would have found that they believed that minorities were more holy than majorities, that failure was nobler than success, which had something shoddy and something vulgar about it. The very notion of idealism, not in its philosophical sense, but in the ordinary sense in which we use it, that is to say the state of mind of a man who is prepared to sacrifice a great deal for principles or for some conviction, who is not prepared to sell out, who is prepared to go to the stake for something which he believes, because he believes in it – this attitude was relatively new. What people admired was wholeheartedness, sincerity, purity of soul, the ability and readiness to dedicate yourself to your ideal, no matter what it was.

Berlin is interested in tracing where all this came from. It was a huge break from the Enlightenment sensibility of the early eighteenth century, which valued reason and consistency. He sums up this older view with three propositions:

First, that all genuine questions can be answered, that if a question cannot be answered it is not a question. We may not know what the answer is, but someone else will.

... The second proposition is that all these answers are knowable, that they can be discovered by means which can be learnt and taught to other persons...

... The third proposition is that all the answers must be compatible with one another, because if they are not compatible, then chaos will result.

These were all thoroughly trashed by romanticism. The rest of the book is devoted to following how this happened.

Assorted ideas from dead Germans

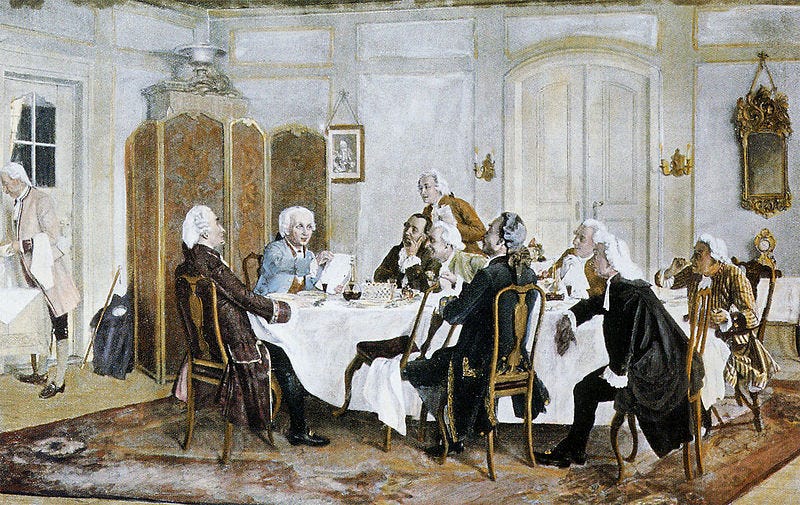

Kant and Friends At Table by Emil Doerstling (1859-1940). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Kant is the one reading from a letter. One of the others is apparently Hamann, but I’m not sure which!

I've stolen this section title from David Chapman's Bad ideas from dead Germans, which is well worth a read. That page and the following series is mostly about the Bad Idea of monist idealism, but it turns out that the romantics had a lot of ideas, which have sort of hung around influencing people in complicated ways ever since. I'm only halfway through and I haven't met all the dead Germans yet, so I'm only going to talk about three of them, who were all early influences on romanticism: Hamann, Kant and Herder. They all lived in Königsberg at the same time, and Hamann and Kant were friends. Herder was a student of Kant, and was some kind of protégé of Hamann as well.

Hamann's easily the most obscure of the three, and, at least the way Berlin tells it, there's good reasons for that:

He was a ne’er-do-well, he was not able to get a job, he wrote a little poetry, and a little criticism; he did it quite well, but not well enough to secure a living; he was supported by his neighbour and friend, Immanuel Kant, who lived in the same city, and with whom he quarrelled for the rest of his life; and then he was sent by some rich Baltic merchants to London, for the purpose of transacting a piece of business which he failed to complete, but instead drank, gambled and got into heavy debt.

As a result of these excesses he was near suicide, but then had a religious experience, read the Old Testament, which his pietist parents and grandparents had sworn by, and suddenly was spiritually transformed.

... In this transformed religious condition he came back to Königsberg, and began to write. He wrote obscurely under many pseudonyms, and in a style which has proved from that day to this unreadable. At the same time he had a very powerful and marked influence upon a number of other writers, who in their turn had a considerable influence upon European life.

From what I can quickly make out from the Berlin book and his Wikipedia article he was mainly notable as a kind of superspreader of the ideas of the time. He introduced Rousseau's work to Kant, translated Hume into German, acted as a mentor to Herder, influenced Goethe and Hegel. His own work was mostly fragmentary and unfinished, but a recurring theme was a deep suspicion of generalisations, concepts and categories:

What they left out, of necessity, because they were general, was that which was unique, that which was particular, that which was the specific property of this particular man, or this particular thing. And that alone was of interest, according to Hamann. If you wished to read a book, you were not interested in what this book had in common with many other books. If you looked at a picture, you did not wish to know what principles had gone into the making of this picture, principles which had also gone into the making of a thousand other pictures in a thousand other ages by a thousand different painters. You wished to react directly, to the specific message, to the specific reality, which looking at this picture, reading this book, speaking to this man, praying to this god would convey to you.

From this he drew a kind of Bergsonian conclusion, namely that there was a flow of life, and that the attempt to cut this flow into segments killed it. The sciences were very well for their own purposes. If you wished to discover about how to grow plants (and even then not always correctly); if you wished to know about some kind of general principles, about the general properties of bodies in general, whether physical or chemical; if you wished to know what climates would assist what kind of growth to develop in them, and so forth; then, no doubt, the sciences were very well. But this is not what men ultimately sought.

If you asked yourself what were men after, what did men really want, you would see that what they wanted was not at all what Voltaire supposed they wanted. Voltaire thought that they wanted happiness, contentment, peace, but this was not true. What men wanted was for all their faculties to play in the richest and most violent possible fashion. What men wanted was to create, what men wanted was to make, and if this making led to clashes, if it led to wars, if it led to struggles, then this was part of the human lot.

So Hamann already has a lot of the key romantic ideas. A focus on the vividness of direct experience, a distrust of science and bureaucracy, a lack of concern for consistency and harmony and general laws (if people want inconsistent things so be it! They can just fight over it), and of course THROWING LOTS OF EMOTION AROUND AT ALL TIMES.

Next up is Herder, who I also knew nothing about. In his case the name did sound vaguely familiar but that was about it. Berlin focuses on three ideas of his:

One is the notion of what I shall call expressionism; the second is the notion of belonging, what it means to belong to a group; and the third is the notion that ideals – true ideals – are often incompatible with one another and cannot be reconciled.

We already saw a bit of the third one with Hamann. The first one, expressionism, is the idea that a work of art should express the nature of its creator. This contrasted with earlier eighteenth century views, where:

... what everyone agreed about was that the value of a work of art consisted in the properties which it had, its being what it was – beautiful, symmetrical, shapely, whatever it might be. A silver bowl was beautiful because it was a beautiful bowl, because it had the properties of being beautiful, however that is defined. This had nothing to do with who made it, and it had nothing to do with why it was made.

This then links to his second idea, that of belonging to a group:

If a folk song speaks to you, they said, it is because the people who made it were Germans like yourself, and they spoke to you, who belong with them in the same society; and because they were Germans they used particular nuances, they used particular successions of sounds, they used particular words which, being in some way connected, and swimming on the great tide of words and symbols and experience upon which all Germans swim, have something peculiar to say to certain persons which they cannot say to certain other persons. The Portuguese cannot understand the inwardness of a German song as a German can, and a German cannot understand the inwardness of a Portuguese song, and the very fact that there is such a thing as inwardness at all in these songs is an argument for supposing that these are not simply objects like objects in nature, which do not speak; they are artefacts, that is to say, something which a man has made for the purpose of communicating with another man.

This is a sort of nationalism, and presumably influenced later, much more damaging kinds. It's easy to read this knowing what came later as an argument for hereditary racial differences, but Herder's version is a culturally transmitted gestalt:

Herder does not use the criterion of blood, and he does not use the criterion of race. He talks about the nation, but the German word Nation in the eighteenth century did not have the connotation of ‘nation’ in the nineteenth. He speaks of language as a bond, and he speaks of soil as a bond, and the thesis, roughly speaking, is this: That which people who belong to the same group have in common is more directly responsible for their being as they are than that which they have in common with others in other places. To wit, the way in which, let us say, a German rises and sits down, the way in which he dances, the way in which he legislates, his handwriting and his poetry and his music, the way in which he combs his hair and the way in which he philosophises all have some impalpable common gestalt.

Most importantly, Herder isn't interested in demonstrating the superiority of any of these national groups:

Herder is one of those not very many thinkers in the world who really do absolutely adore things for being what they are, and do not condemn them for not being something else. For Herder everything is delightful. He is delighted by Babylon and he is delighted by Assyria, he is delighted by India and he is delighted by Egypt. He thinks well of the Greeks, he thinks well of the Middle Ages, he thinks well of the eighteenth century, he thinks well of almost everything except the immediate environment of his own time and place. If there is anything which Herder dislikes it is the elimination of one culture by another. He does not like Julius Caesar because Julius Caesar trampled on a lot of Asiatic cultures, and we shall now not know what the Cappadocians were really after. He does not like the Crusades, because the Crusades damaged the Byzantines, or the Arabs, and these cultures have every right to the richest and fullest self-expression, without the trampling feet of a lot of imperialist knights. He disliked every form of violence, coercion and the swallowing of one culture by another, because he wants everything to be what it is as much as it possibly can.

This is where the third idea of incompatibility comes in. He sees each of these cultures as expressing its own nature, and doesn't care at all about whether these natures are incompatible. He doesn't expect at all that there should be some clean tidy general answer about 'how humans should live' - that question is meaningless for him. Which is a Big Deal:

This is a very new and extremely revolutionary and upsetting note in what had for the last two thousand years been the solid philosophia perennis of the West, according to which all questions have true answers, all true answers are in principle discoverable, and all the answers are in principle compatible, or combinable into one harmonious whole like a jigsaw puzzle. If what Herder said was true, this view is false, and about this people then proceeded to argue and to struggle, both in practice and in theory, both in the course of national revolutionary wars and in the course of violent conflicts of doctrine and of practice, both in the arts and in thought, for the next hundred and seventy years.

So finally we come to Kant. I'd never associated him with romanticism at all... his early work was in physics, he's famous for writing dense, difficult treatises about technical topics like space and time and causality, and of course for taking the same walk around Königsberg at the same time every day. These are not very romantic things to be doing. And indeed he had little patience for the romantic temperament:

He disliked everything that was rhapsodical or confused in any respect. He liked logic and he liked rigour. He regarded those who objected to these qualities as simply mentally indolent. He said that logic and rigour were difficult exercises of the human mind, and that it was customary for those who found these things too difficult to invent objections of a different type.

However, he ended up being a huge influence on later romantic thinkers anyway. Berlin argues that a large part of this comes from something I hadn't appreciated at all about Kant. Alongside all the technical causality stuff, he was apparently passionately committed to human freedom from determinism:

In the case of Kant it became an obsessive central principle. Man is man, for Kant, only because he chooses. The difference between man and the rest of nature, whether animal or inanimate or vegetable, is that other things are under the law of causality, other things follow rigorously some kind of foreordained schema of cause and effect, whereas man is free to choose what he wishes.

This fed into his political views:

Once man was encouraged, as he was by the French constitution, to vote freely in accordance with his own inner decision – not impulse, Kant would not have called it that – his own inner will, he was thereby liberated, and, whether Kant interpreted it correctly or incorrectly, it appeared to him that the French Revolution was a great liberating act, inasmuch as it asserted the value of individual souls. He said much the same about the American Revolution too. When his colleagues deplored the Terror, and regarded all the events in France with undisguised horror, Kant, although he did not exactly openly approve, never quite retreated from his position that it was at any rate an experiment in the right direction, even if it went wrong.

The sort of worldview that that goes along with this is also interesting. Humans are divided into a kind of animal part that obeys fixed causal laws (this would include the body and the emotions), and a higher part that has the ability to choose freely and impose its will on the world. This suggests a more fraught relationship with nature than that of the early eighteenth century, where nature was considered as a more-or-less harmonious system:

... nature in Kant becomes at worst an enemy, at best simply neutral stuff which one moulds. Man is conceived of as in part a natural object: plainly his body is in nature; his emotions are in nature; all the various things which are capable of making him heteronomous, or depend upon something other than his true self, are natural; but when he is at his freest, when he is at his most human, when he rises to his noblest heights, then he dominates nature, that is to say he moulds her, he breaks her, he imposes his personality upon her, he does that which he chooses, because he commits himself to certain ideals; and by committing himself to these ideals he imposes his seal upon nature, and nature therefore becomes plastic stuff.

So that's where I'm up to. A huge outburst of ideas about particularism, free expression, national character, the will, new attitudes to inconsistency and incompatibility, and more that I didn't get to. Next up are Schiller and Fichte, it looks like. And probably more (worse?) ideas.

The Newsletter Writer's Audience is Less of a Fiction

I was going to leave this newsletter there but then I remembered another reason I like the newsletter format, and wanted to say something quick about it. This relates back to Ong, who I talked about last month. After finishing Orality and Literacy I read a paper of his, The Writer's Audience is Always a Fiction, which talks about the problem of figuring out who you're writing for. He gives the example of a school student who is struggling to write an essay on 'How I Spent My Summer Vacation'. The subject matter might be familiar, but the student still has to solve this problem of who the audience is:

The answer is not easy. Grandmother? He never tells grandmother. His father or mother? There's a lot he would not want to tell them, that's sure. His classmates? Imagine the reception if he suggested they sit down and listen quietly while he told them how he spent his summer vacation. The teacher? There is no conceivable setting in which he could imagine telling his teacher how he spent his summer vacation other than in writing this paper, so that writing for the teacher does not solve his problems but only restates them. In fact, most young people do not tell anybody how they spent their summer vacation, much less write down how they spent it. The subject may be in-close; the use it is to be put to remains unfamiliar, strained, bizarre.

Figuring this out can be a pain, but for some reason I find it easy to solve when writing a newsletter. I don't normally have a particular person in mind, but I do have some sense of who I know that might be interested in the topic, and I drop very easily into a conversational voice. In fact, I notice that earlier in this section I wrote that I 'talked about' Ong last month, not that I 'wrote about' him. I didn't consciously choose to express it that way, so it must just be how I'm naturally thinking about it.

Anyway this makes the newsletter easy and fun to write. My blog post style tends towards the casual and conversational too, but there still seems to be a bit more distance in there. I don't fully understand what makes them feel different though? If you have any more insight into this let me know.

Next month

... I am FINALLY going to get this sodding Bell's theorem post out. It's pretty close now. Then there's a follow-up post, 'Worse than quantum mechanics', which should use some of the stuff I explained in the Bell post. In my head that feels like it will take a few hours, which probably means it'll actually take several months.

I'll probably finish The Roots of Romanticism too. So I might continue with more assorted ideas from dead Germans next time, or maybe I'll want to talk about something else.

Again, feel free to leave comments, or reply to this, or contact me elsewhere. I'm kind of slow and inconsistent at replying but I mostly get there in the end!

Cheers,

Lucy