December 2020: if it's the end of the year, then I write a review

The Wason selection task, a big web of recommended texts, and my end-of-year review

Well, so that’s over. This newsletter has some of the classic end-of-year type stuff at the end. There’s also a section on yet another psychology experiment that turns out to be More Complicated Than I Thought.

I’d already decided last month that I’d drop the physics blog post that was annoying me and think about something else for a while. The main thing I ended up doing was making a big twitter thread… this was more productive than it sounds.

100 text links

I took part in Threadapalooza this year, a twitter thing where you write a 100-tweet thread on a topic of your choice. I stole an idea from David MacIver, who had previously done a thread of 100 pairings between books. I expanded this to include internet writing as well - blog posts, articles, random pdfs and the like. This made it easier, and was also a better fit for me in general - lots of my favourite texts are on websites somewhere, and I don’t clearly distinguish between web text and books in my head anyway.

It turned out to be pretty time-consuming, and I dribbled out links slowly over the next week or two. I got bored near the end but it was mostly surprisingly enjoyable. There was a subtle effect that I wasn’t expecting. All these links are normally sort of a murky background soup of influences that I live inside without actually seeing, but writing them down explicitly brought them to the foreground for once. It was like zooming out and seeing an aerial view of my whole home on the internet for the first time.

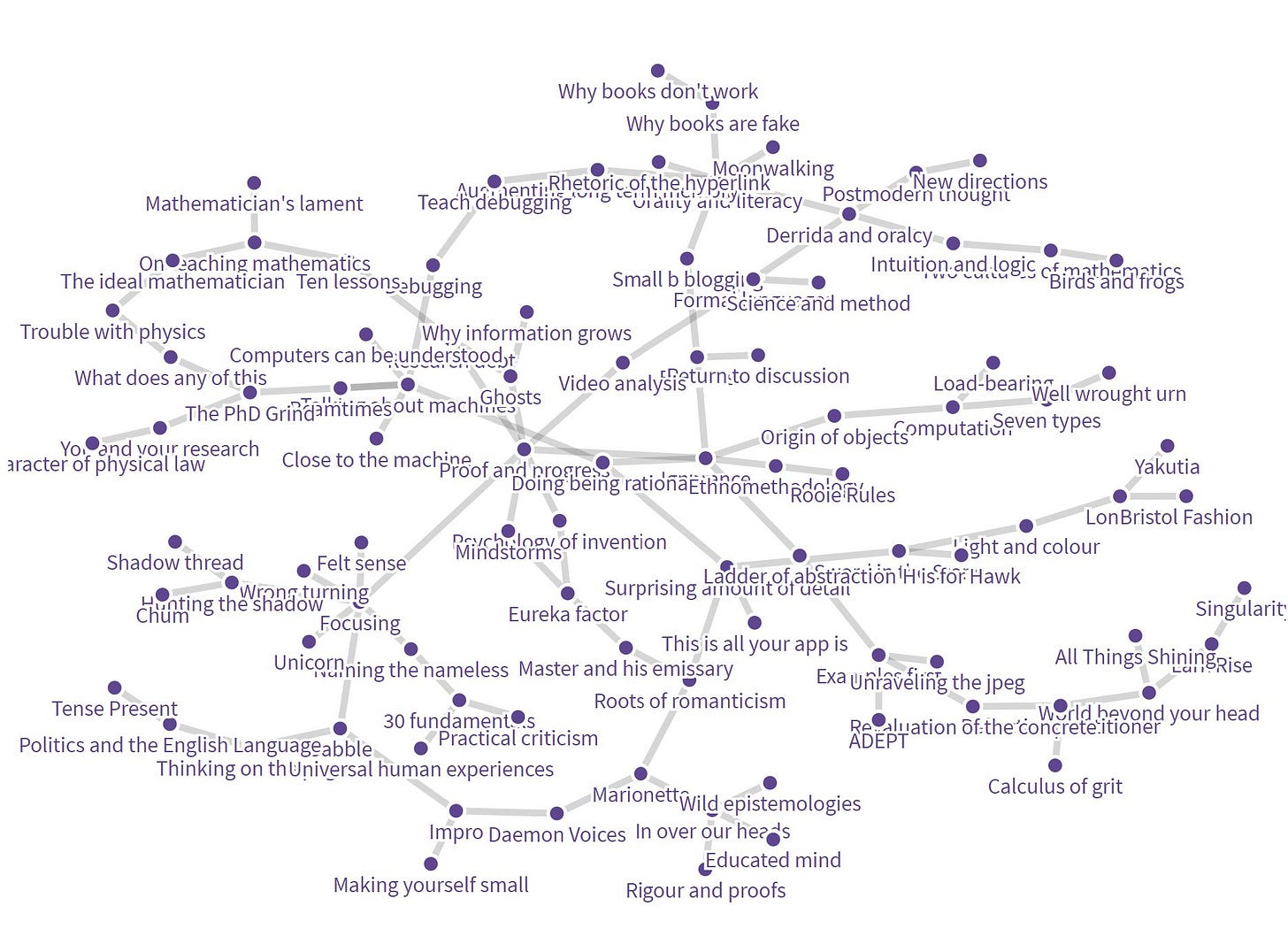

Here’s the final graph:

And here’s a clickable version of the graph, and a link to the start of the thread.

Cognitive decoupling and the Wason selection task

Threadapalooza was also good for getting me to go back to some texts and find new things in them. One book I revisited is Catarina Dutilh Novaes’s Formal Languages in Logic, which I bought a while back but only read a small chunk of. This time I picked it up somewhere in the middle and immediately came across something Relevant To My Interests.

There’s a famous psychology experiment called the Wason selection task. Participants are shown four cards — Dutilh Novaes takes

[A], [B], [4], [7]

as her example. They’re also given a rule, in this case:

If a card has an even number on one side, then it has a vowel on the other side.

They then have to figure out which cards to turn over to verify the rule.

Basically everyone turns over the [4]. If you’re interpreting this in terms of classical logic then you should also turn over [B], because if that has an even number on the other side then the conditional doesn’t hold.

Generally people don’t turn over the [B] though. Typical results are apparently something like this:

35% just turn over [4]

45% turn over [4] and [A]

only 5% turn over the ‘correct’ response of [4] and [B]

Now I got mildly interested in this experiment a couple of years ago when someone pointed it out in connection with the bat and ball question from the Cognitive Reflection Test, which I spent far too long thinking about a couple of years ago. The interesting feature of it is the following: people do much better with a set of cards marked [Manchester], [Leeds], [train], [car], and the rule:

Every time I go to Manchester I travel by car.

This time people are much more likely to realise that, as well as turning over [Manchester] to check it has ‘car’ on the other side, they also need to turn over [train] to check it doesn’t have ‘Manchester’.

I’d previously come across this result (with the beer version of the rule, ‘if you are drinking alcohol you must be over 18’, where the ‘right answer’ feels particularly intuitive and accessible to me) and had taken this to be a case of ‘cognitive coupling’, where simply adding real world information makes the problem easier. I mentioned it briefly in my cognitive decoupling and banana phones post, but didn’t look into it very carefully.

It turns out that the actual situation is more complicated than that. Just replacing all the numbers and letters with everyday items, to get a sentence like ‘If I eat pork, then I drink wine’, apparently didn’t change much. So it’s something more specific that creates the effect.

Some clues as to what creates the effect came from an experiment in the UK in the 70s, where the rule was:

If a letter has a second class stamp, it is left unsealed

Apparently this was an actual rule in the UK at the time (wtf?? why?) and British people did much better at realising they also had to turn over letters with sealed envelopes to check the stamp type. This didn’t replicate in the US, where the rule was unfamiliar. The same US participants did fine with the familiar beer rule though.

So it’s a pretty complicated situation. I’m not going to go through all the variants and competing explanations that Dutilh Novaes lists, that would take too long, so I’ll focus on one point I found interesting.

It’s easy to imagine that these natural language rules automatically map to one particular logical statement, like ‘even ⇒ vowel’ or ‘Manchester ⇒ car’, and that the participants are just getting it wrong if they come with a response that doesn’t match the logical conditional. Dutilh Novaes says that

… psychologists typically rely on a fairly naive understanding of the concept: the logical form of a sentence or argument would straightforwardly be ‘read off’ from its surface structure.

But language is not really that transparent, and there’s more going on in these rules than just a pure ‘if … then’ structure. She references a book by Stenning and van Lambalgen, Human Reasoning and Cognitive Science, that points out one of these complicating factors.

There’s a difference between ‘descriptive conditionals’, which just describe a particular regularity (like ‘if I eat pork, then I drink wine’), and ‘deontic conditionals’ which describe how things ought to be (like ‘if you are drinking alcohol you must be over 18’). These are subtly semantically different:

For a descriptive conditional, if you turn over a card that doesn’t fit the rule, then it’s just false. So turning over a card can affect the status of the rule itself.

For a deontic conditional, if you turn over a card that doesn’t fit the rule, then the rule is not false, just violated. (A 15-year-old drinking beer doesn’t make the rule false, it just means the 15-year-old isn’t obeying it.) So turning over a card never affects the status of the rule.

Notice that sentences don’t have to unambiguously map to one category or the other. Take the sentence in the newsletter title, ‘if it’s the end of the year then I write a review’. Is this a description of a regularity, that could be shown to be false in 2021 if I don’t bother? Or would skipping it in 2021 involve me breaking the rule, which is itself unaffected? Some interpretation based on context is needed.

The two types of conditionals are different enough conceptually that it’s maybe not surprising that we treat them differently (without necessarily having to bring in elaborate evopsych explanations about detecting cheaters, as other researchers have done).

I still feel a little confused about why we end up matching the standard logical answer in the deontic case, but not the descriptive one. Dutilh Novaes says that ‘the task arguably acquires a structure that is easier to process by the participant’ and that conditionals in general tend to get interpreted in this way, as rules that can be broken. But it still feels unclear to me. Maybe reading some of the source text would help.

End-of-year review

I’ve done this here the last couple of years, focussing on the blog, newsletter and any physics stuff I’ve been doing, and it’s been sort of useful, so I’ll do a quick one again. This has been such a weird year that I quickly gave up on having any particular expectations for it, and just churned out whatever I felt up to doing. The blog and newsletter suffered for it, physics maybe came out ahead but it’s too early to say, overall ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ I’ll take it.

Blog

Well, I wrote more posts than usual, I suppose I can say that for it. Unfortunately these were almost all written in June as an experiment in writing short fast low-quality ‘notebook’ pieces. There were a few good ideas in there, and it was worth trying something different, but overall nothing special. I already wrote a bit about those here.

Outside of that, hmm, what have I written? Pre-plague I posted The shitpost-to-scholarship pipeline, about the difficulties of going deep with research outside of academia. That was mostly written already in 2019 as part of a newsletter, I just cleaned it up and reposted with some stupid images as something to talk about at Jess’s Sensemaker Workshop in London. I also posted up some notes on a paper about eighteenth century mathematics. Again, those were prewritten and I just tidied them up a bit.

After that, nothing until notebook month (too busy doomscrolling) and after notebook month I only wrote two more posts. One was a quick post learning about the psychologist Vygotsky and his collaborators using a ‘speedrun’ find-out-what-you-can-in-an-hour format I tested during notebook month. The other was the only high-effort post I wrote all year, a long post on Bell’s theorem and Mermin’s machine. I’ll cover that under the Physics section.

So… pretty bad compared to previous years in terms of substantial thoughtful work, but I kept the blog alive and haven’t forgotten how to press the Publish button, so that’s a win I guess.

Newsletter

I took a break from the newsletter at the start of the year because I was stressed out with work and not enjoying it much. In July I restarted it on Substack, and it’s been going… ok, I guess? The Orality and Literacy and Examples First ones are probably the best.

On average they hasn’t been as good as the previous round of newsletters, and they’ve mostly been written quickly at the end of the month rather than being developed over the whole month, so they feel a bit shallower and more disconnected from what I’m thinking about day to day. I still want to keep the newsletter going though, to keep the habit of writing consistently. It hasn’t felt annoying or like a chore, just a bit uninspired most months.

Physics

This was my main focus for the year, but looking back it’s really hard to evaluate. Partly because everything is still half-baked and it’s too early to tell whether anything works or not, but also because I’ve had a month off and everything has fallen out of my head. Let’s try and remember what I did…

I don’t think anything much got done in January. In February I had the month off twitter and blogs and was very productive. I had an idea for a toy model that’s definitely interesting, but I’m not sure how far it goes. Unfortunately I dropped that completely during early March covid panic and haven’t seriously gone back to it, though I’ve thought about it a little bit in background mode.

My brain rebooted in May or so but got fixated on a different topic, some papers by Samson Abramsky and collaborators that I was trying to skim on the bus several months earlier. I’d been missing some mathematical background and had fun learning some basics about sheaves and cohomology out of whatever example-based sources I could find. I didn’t learn enough to fully understand what I want to understand, but I got a lot further, and started writing a long expanded version of the stupid dialogue about chips, beans and peas from my Bell post to explain the bits I did get. Not sure I’ll ever finish but I think the world will survive without it somehow.

Also as part of the Abramsky paper reread I worked through some of his paper with Lucien Hardy on logical Bell inequalities, and realised that it gave me the tools to finish an idea that I’d had back in 2018. I’d wanted to write a blog post that explicitly showed how to go between Mermin’s very intuitive pop-science explanation of the Bell inequalities, and the standard CHSH inequality you see in textbooks. Adding in a middle link using the logical Bell framework made this much easier and I finally got the post done. I’m pretty happy with that one, but maybe I should have split it into parts or something, so that more people would actually read it? I don’t know… strategy is not my strong point.

I also got a second idea out of the logical Bell thing, and I’m writing it up currently. I can’t find it in the literature but can’t tell whether it’s generally known but not written down, or written down somewhere obscure, or just less interesting than I think it is. I got really bogged down in writing this up and decided to give myself a month off thinking about it, but I’m starting to want to look at it again.

Overall there’s a lot going on. Reading last year’s review back, it looks like I was pretty pessimistic and starting to despair of being able to do anything like ‘proper research’ in my spare time. This year there was some sort of transition, and I just started having more ideas without particularly trying hard. So I’m cautiously optimistic again that I can actually do something interesting.

I was hoping to travel to at least one workshop this year and meet some people from the physics society I’m in… unsurprisingly that didn’t happen. Still really want to do this! I’ve also failed to get any better at contacting people in academia to ask questions, so that’s also still a project for next year.

Next month

I’m taking a month off Twitter. I’ve been doing this every year or so and I normally get a lot done and find some new interesting things to read. Feels like I’m ready for another one. The plan is to go back to this physics blog post I stalled on in November, and try and make progress.

Next year

In general 2021 feels particularly up in the air, partly from covid uncertainty and partly because my plans are in a sort of confusing mushy unresolved state in general. I’m doing Malcolm Ocean’s Goal Crafting Intensive course on Sunday, in an attempt to get myself to think clearly through the possibilities and hopefully get some advice and new perspectives from others.

The one thing I know I want to do is TRAVEL AND SEE PEOPLE! That won’t be for some while yet, I know, but I’m really looking forward to it already. It would be great to catch up with some of you I’ve met before, and meet some new people from Twitter and here.

Happy new year,

Lucy