June 2024: improvise like it's 1799

An infodump on 18th century musical pattern languages, which is apparently what I'm interested in now, why is my brain like this

I had no trouble deciding what to write this time. In late April I fell down a weird rabbithole to do with music teaching methods in 18th century Italy, and I’m still in there.

It started fairly innocuously when I just wanted to find out a bit more about a style of music I like, and typed “galant style” (I’ll get to what that is in a bit) into Google Scholar. This brought up a book that looked promising, Music in the Galant Style by Robert O. Gjerdingen, which turned out to have this excellent frontispiece and dedication:

Obviously I then went to look for where this stuff was “Collected for the Reader’s Delectation on the World Wide Web”, and found the accompanying website1, a proper enthusiast’s one from the 00s with little skeuomorphic green buttons to click on:

This website introduced me to partimenti, musical sketches used as teaching materials. Students would learn improvisation and composition by filling out the rest of the piece.

OK, so then I had to look up what else I could find on partimenti. It turns out that there’s been a revival of interest in teaching this way in the last ten years, so there are lots of YouTube videos and other resources to learn from. In fact... why don’t I just learn this myself? The teaching materials were originally designed for young students, so they start at a level that’s within the reach of my basic piano skills.

So next thing I know I’m spending my spare time for several weeks learning something called the Rule of the Octave, while watching and reading a load of related materials. It’s actually one of the most intense weird obsessions I’ve ever had, on something I had no idea even existed six weeks ago. Kind of bizarre.

I’m out of the acute phase now and want to write it up before it fades into a more normal level of interest, so I’m going to subject you to a long infodump on what I’ve learned. I guess this is obvious, but quick boring disclaimer, I have not been learning about this for very long and might get some things wrong.

Galant music

I’ll start with a little bit on what the galant style is. In modern terminology, you might describe it as a transitional period between what we’d now call the classical and baroque. Gjerdingen points out, though, that nobody at the time used the terms “baroque” or “classical”:

These terms were developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries for the purposes of those later times, but they obscure rather than illuminate eighteenth-century music.

“Galant”, however, was a term that was popular in the eighteenth century:

It referred broadly to a collection of traits, attitudes, and manners associated with the cultured nobility. If we imagine an ideal galant man, he would be witty, attentive to the ladies, comfortable at a princely court, religious in a modest way, wealthy from ancestral land holdings, charming, brave in battle, and trained as an amateur in music and other arts... His female counterpart would have impeccable manners, clothes of real sophistication, great skill as a hostess, a deep knowledge of etiquette, and training in one or more of the “accomplishments” – music, art, modern languages, literature, and the natural sciences.

So galant music was the music associated with this sort of aristocratic culture. It was in high demand and churned out in large quantities:

The composer of galant music, rather than being a struggling artist alone against the world, was more like a prosperous civil servant. He typically had the title chapel master... and managed an aristocrat’s sacred and secular musical enterprises. He worried less about the meaning of art and more about whether his second violin player would be sober enough to play for Sunday Mass. The galant composer necessarily worked in the here and now. He had to write something this week for an upcoming court ceremony, not tortured masterworks for posterity.

Maybe these quotes are making galant music sound kind of terrible… mannered and artificial, a sort of bulk commodity supplied to the rich. That’s probably not totally wrong, but anyway, I really like the good bits. Galant music tends to have a lot of good melodies, in part because it had to be immediately appealing to its audience. There’s no Bach-style cerebral counterpoint or complicated Romantic harmonic progressions, so generally a piece of galant music will make sense on the first or second listen. The interest is more in the moment-to-moment texture of the music and the delicate emotional shading.

Mozart and Haydn both have a strong galant influence to their music, but the canonical galant composers tend to be smaller names who aren’t played so much now. Here are some examples I like, with links to their music:

Baldassare Galuppi was a Venetian composer who was incredibly popular in his lifetime but not listened to much now (he’s possibly more famous for being mentioned in this Robert Browning poem). I don’t know why, but Ensemble ConSerto Musico’s recording of his harpsichord concertos is basically the ideal form of music according to some corner of my brain. This first one in particular has become my standard comfort food music, I’ve possibly listened to it more than any other recording of anything.

I’m currently listening to a lot of Johann Christian Bach (not Johann Sebastian). So far I particularly like the “Berlin” harpichord concertos, here’s an example.

Last year I had a phase of listening to Johann Schobert (not Franz Schubert), who was a major influence on Mozart. The other thing he’s known for is killing himself and most of his family by eating mushrooms that he’d been repeatedly told were poisonous, see Wikipedia for the full story. This harpsichord sonata is an example of what I was listening to.

I’ve been listening to this sort of music for several years now, but didn’t have much idea of how this music developed or what really held it together as a style. Music in the Galant Style has made it all make more sense.

I’d already noticed that most galant composers were either Italian or had studied in Italy, and that there were some complicated lineages of Italian teachers who had spread this style around Europe. I remember discovering Charles Avison and thinking he sounded weirdly Italian for someone who spent most of his life in Newcastle, and it turned out that he had an Italian teacher, Francesco Geminiani.

Gjerdingen’s book has given me a better understanding of at least part of how this happened. Italian schools had developed particularly good teaching methods, and produced lots of highly trained musicians who were then exported across Europe. In particular, Naples was a big centre. There were several charity schools for orphans that were something like musical trade schools, training their pupils to be court musicians and chapel masters so that they had a way to support themselves.2

The schools used teaching methods that are very practical and still look to work well today, judging by the small YouTube subculture that’s grown up around them. So I thought I’d have a try at learning this way myself.

Partimenti

I’ve mainly been working towards something called partimento practice. A partimento is basically just a bassline, something you’d play with the left hand at the keyboard. For example, Fenaroli’s partimento no. 30 starts like this:

The idea is that you’d then put chords and melody on top of the bassline, turning it into a full composition or improvisation (this is called “realisation”). Here’s an example realisation for this particular partimento, with the given bassline shown at the bottom of the screen:

This is a pretty advanced partimento (and a very fancy Scarlatti-inspired realisation, too). To be able to realise something like this, you first need to work through a lot of prerequisites.

For a start, you need to be able to understand figured bass, the standard way of notating chords at the time.3 I already had a rough grasp of figured bass, so I started on the next most basic thing to learn, something called the Rule of the Octave. This gives you standard chord progressions to go with ascending and descending scales, a kind of basic musical language that you use by default if there isn’t anything more specific going on.

The exact details vary a bit between sources, but the rough idea is that the first, fifth and octave of the scale are stable points that you put a solid chord on with a third and fifth above the bass. The other notes take some kind of slightly weaker sounding chord with a sixth above the bass. Immediately before the stable points, you introduce an extra dissonant note to the sixth chord to increase the tension before resolving it. (This is why the rule is different ascending and descending, you approach the stable points from different sides.) There’s one more complication where the third note in the scale is treated as a sort-of-stable point, so the note before it also gets a dissonant chord.

You end up with something like this (source):

The numbers below the coloured shapes are the figured bass, telling you what intervals above the bass note to play. Roughly speaking, more figures = more dissonant.

I’ve been spending a lot of time practising the Rule of the Octave. “Rule” makes it sound like something theoretical, but really the main work is to get the chords into muscle memory so that you can play the correct chords fluently when you see the corresponding notes in the bassline.

This is quite a lot of work in itself. There are three positions to learn for each scale that shuffle the notes in the right hand chord around, so if you learned five major and five minor keys (not really very many) then that’s 30 different scales. Obviously the process speeds up as you get used to the sounds of the different chords, but it’s not quick and I still have a long way to go.

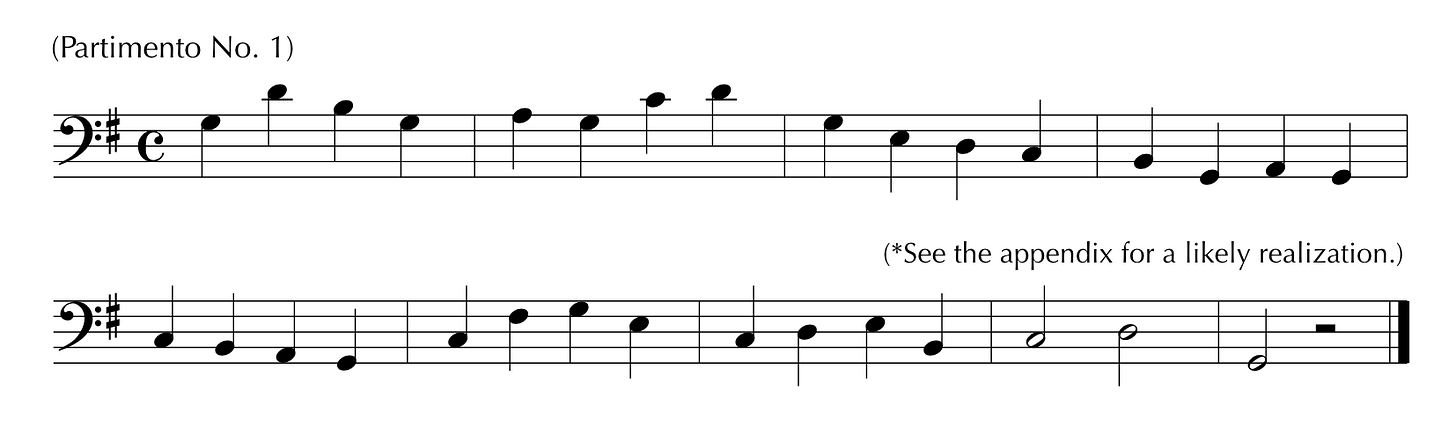

The Rule of the Octave is enough for the “baby’s first partimento” stage, where you put block chords or simple melodies above a slow-moving bass line. This is the point I’ve just started to reach. I’m working on the classic starting point, the first partimento from the book by Furno:

As you can see, it’s a lot simpler than the one I showed earlier. There’s still a lot of room for skill and taste though. Partimenti aren’t single-solution exercises that you complete for good and move on from. A skilled player can take the same partimento that I’m clumsily plonking chords on top of and turn it into something actually good.

After learning the Rule of the Octave, there are more rules, on things like how to modulate to different keys, what to do at the end of a phrase and how to treat different intervals in the bass. The early stuff is fairly formulaic, but as a player progressed they’d develop their taste and learn how to combine more complex patterns in interesting ways.

Schemata: a galant pattern language

Patterns are the main subject of Gjerdingen’s Music in the Galant Style. Each chapter names and discusses a particular pattern – the Fonte, the Monte, the Ponte, the Prinner – and gives a ton of examples. (Maybe half the book is music excerpts.) Some of these patterns were named back in the 18th century, others are new names for other common patterns that Gjerdingen noticed. He refers to these patterns as “galant schemata”, comparing them to similar stock themes in fairy tales or commedia dell’arte.

Schemata are short repeating stretches of musical material – normally a series of notes that the bassline should hit, with corresponding melody notes on top – on the order of a few bars long, that serve standard purposes, similar to “once upon a time”, or “a poor woodcutter lived in the forest”. For example, there are patterns for opening a piece, for responding to the opening phrase, and for modulating into a different key.

Schemata are normally embellished and varied, so that different interpretations of the same schema can end up sounding very different. For example, here is a collection of examples of the Prinner pattern, a response phrase where the main feature is a 4-3-2-1 downward movement in the bass:

Some of these, like the third and fourth excerpts, have very easy-to-hear “bam bam bam bam” answering 4-3-2-1 phrases. In others, it’s a lot more subtle and you’ll have to listen out for it.

Students would develop their taste by using these patterns in different contexts, under the guidance of a skilled maestro:

… in the training of young musicians in conservatories, it was not enough for a master simply to show an exemplar of a schema and then to expect a boy to learn it. Instead, a schema would be introduced in the context of a longer exercise. In a partimento, for instance, a schema might be presented as a bass pattern at the opening to be played in the left hand. The boy would need to learn how to improvise a right-hand part that fulfilled or “realized” the implications of that schema. In the course of the next thirty to sixty measures of the partimento the same schema would recur in different keys or with small variations. As the boy worked through the lesson he gained a more complete and richer understanding of what that schema entailed.4

It turns out that this method still works well today! We don’t all have the guidance of a skilled maestro, but we do have YouTube. And there’s a small dedicated subculture of musicians who are teaching and learning this stuff together.

I’m not quite sure why partimenti and schemata have had a surge in popularity. Maybe some of it is just that YouTube has been great for weird little practice-based communities of all kinds. But I think part of it is that the famous young pianist Alma Deutscher learned in this way as a child, under the teaching of the musicologist Tobias Cramm. This video of them improvising together over video call from when is incredible:

There’s something strangely moving here that I struggle to describe. I love how much they seem to be enjoying themselves, and how they can understand each other’s intentions well enough to blend their improvised passages into a composition that flows naturally even over a video call. But more than that, it’s wonderful to see this tradition that I’ve been reading about in an academic text suddenly alive in front of me, from a child the same age as the orphans in the conservatories of Naples. She’s not just playing finished music in the galant style, written by great composers from the past, but spontaneously creating the raw material that produced that finished music. It’s maybe not surprising that she’s become a composer as well as a pianist.

It also just… makes galant music make sense? There’s this sort of melodic abundance to it that just sounds like there are patterns bursting out of every corner and elaborating themselves. Kind of mad in retrospect that I’d tried to understand it by just listening to completed pieces.

Links

This section is mostly for my benefit – I’ve watched and read a ton of stuff this month and would like to have a list of my favourites to refer back to. But maybe if you’ve got this far you’ll find some of them interesting too. This list covers some references I linked to above, and a few new ones.

I’m normally more of a text person, but this subject absolutely needs audio so there are a lot of videos.

General

My main two sources for this post are both by Robert Gjerdingen:

his book, Music in the Galant Style

his website, partimenti.org

Rule of the Octave

The partimenti.org site has PDF guides to what the Rule of the Octave is and how to learn it.

I found this Music Matters video helpful when I started. It’s sort of a rational reconstruction of the rule in modern music theory terms, starting by putting root chords above every note in the scale, noticing it sounds crap and slowly changing chords until it works. Only covers the ascending scale.

This Early Music Sources video is a more historically informed introduction:

Partimenti

Another Early Music Sources video, Partimento – Training the Maestri, is a good introduction to what they are.

The partimento.org site has a big collection of partimenti and lots of supplementary information, including a guide to how to learn them.

The Fenaroli partimento realisation video I included is one of several from the En blanc et noir YouTube channel. Also, this guy is just funny, look at these notes from his Scarlatti video:

Galant schemata

Music in the Galant Style is mostly about galant schemata.

The Prinner collection I linked above is one of several collections of galant schemata on that channel.

Here is another link to the video of Alma Deutscher and Tobias Cramm improvising:

If you watch one thing from this list, watch the Alma Deutscher video!

The site I linked above is actually a rehosted copy of some of the original website, which was originally hosted at Gjerdingen’s academic site at Northwestern and got replaced with a link to the Internet Archive when he retired. It’s missing the associated audio files (and probably other things), so if you want the full experience you have to go to the archived version and put up with it being slow.

Gjerdingen has a second book about these schools specifically, Child Composers in the Old Conservatories, which I haven’t read.

I was learning a lot of music theory last year, and resisted learning figured bass for a while because I assumed it was just an older, crappier notation for chords that got replaced for good reason. But actually it’s more like a different coordinate system that gives you a new way of thinking, in terms of intervals above the bass note instead of inversions of a root chord, and that’s highly adapted to improvising above a bassline. This video got me started on understanding the point of it.

From Gjerdingen’s What are schemas? (pdf)

Very cool - I might try it!

My classical guitar teacher is big on improvisation (he plays jazz too) and he got me onto Nicola Pignatiello. He has tutorials on his YouTube channel and he's released an edition of Fenaroli edited for guitar. Trying to read figured bass on the guitar just sucks though