February 2024: Notes on "Notation Must Die"

No physics for once! Instead let’s have some music theory

OK, change of topic this month. I recently watched Notation Must Die: The Battle For How We Read Music, by the composer and music software designer Tantacrul. It's about western classical music notation and various attempts to reform it by people who think it's too complicated and inaccessible. Some of these people are enthusiastic nerds who think "I bet I could fix this, how hard could it be", others are grifters who've found a way to market their terrible software to beginners, but either way Notation is Bad and Must Die. On the way he explains some of the history of musical notation and the tradeoffs that went into developing it, which help to explain where all the complexity comes from.

One example from the video: music spans a large range of frequencies, so classical notation splits this range into shorter bands and labels them with clefs. Some reformers hate clefs because they're an extra thing to learn – why not drop the extra complexity and just draw a lot of extra lines on your staff so that all instruments can use the same one? And yes, that drops a piece of notation, but also most instruments only use a particular frequency range and that's exactly what the clefs are adapted to. So then you end up with a lot of empty space which you can only get rid of by zooming in and indicating which bit you're going to use... at which point you're halfway back to clefs. This doesn't mean you can't do better than clefs, which are a bit weird and awkward, but you do have to have some sort of notational convention, or accept the tradeoff of masses of useless lines. And of course this is only one tradeoff, and there are plenty of others that interact with it – the video goes over several.

Anyway the video's great and so is the whole channel. I'm slowly working through his videos and enjoying them a lot. And this all sounds very relevant to my interests in writing and mathematical notation, so let's see whether I can pattern match ideas from the video to the usual sort of stuff I go on about. I’ll find out what I think as I go.

Spectrograms and cat pictures

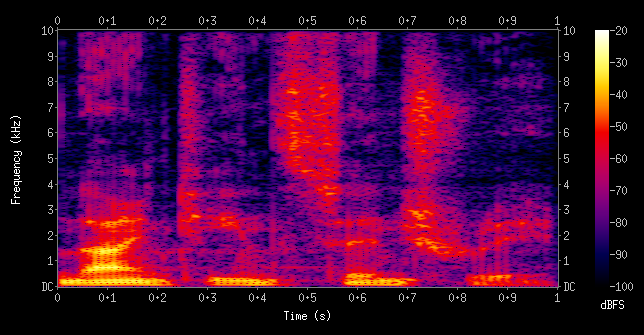

So, one axis of variation for music notation systems is how much complexity they keep in. At one extreme end you could keep in as much as possible, maybe by literally printing out a spectrogram of how the frequencies change over time.1

Even making a spectrogram requires a bit of interpretation because the whole idea of time-frequency diagrams is slightly fake, and there are lots of choices for how to define the spectrogram with different tradeoffs, but most choices will keep a huge amount of information in. Enough to cover any kind of music you want, not just western classical music but any other tradition, or any kind of modern experimental music.

The obvious downside is that it's going to be a giant unreadable mess with far too much going on. But actually theres's a worse downside, which is that all that detail is not even useful. A spectrogram is a good way to record an individual performance, because it records exactly what happens at every point in time. But a piece of music is more than a single performance. It's something that can be played multiple times by different people in different places, without sticking rigidly to having exactly the same thing happen every time. At the very least there should be some allowance for slightly changing the tempo, or for playing different instruments with subtly different timbres, or for tuning slightly flatter or sharper. The spectrogram can't represent any of this because it's completely locked to a single context.

The other extreme, where you completely ignore any characteristics of the music and instead draw e.g. a picture of a cat, is obviously even more useless than the spectrogram. We need to get some freedom from context so that we're not stuck repeating a single performance, without ending up so free that we have no idea what the music is supposed to sound like. This is the space where notation comes in.

Short infodump about my usual pet topics

There are two different vocabularies I like for thinking about this tension. One is Brian Cantwell Smith's idea of "the middle distance" in On the Origin of Objects, which I wrote about here. Useful notation is somewhere in the middle distance between the spectrogram and the cat, not rigidly causally linked and not completely unrelated either.

The other is super obscure. I got it from this paper by Gordon Bearn that I fished up from Google Scholar. Bearn talks about how representations must broach the possibility of meaning, by providing some link at all to the thing they represent (this is what the cat fails at). At the same time they must also breach their context by getting some distance from it (this is what the spectrogram fails at). Bearn gets the broach/breach word pair comes from an inspired translation of Derrida, I summarise the background here.

One standard way that notation breaches context, avoiding the lock-in of the spectrogram, is to make use of the fact that music has regularities. We don’t actually sing or play any old frequency we like, we split the range into defined notes in a scale. We define set note lengths and rhythms rather than burbling at random.2 So notation can often use a discrete set of symbols to represent these fixed reference points, rather than having to deal with the whole continuous range. Some examples would be quarter notes/crotchets to represent a particular note length, or lines of a staff to represent a particular pitch.

These reference points allow you to get a bit of freedom from the details of any particular performance. If you hit the most of the right reference points in the right order, you’ll hopefully produce something that sounds enough like the intended piece of music. There are lots of ways to do this, which means that different musicians can read the same notation and create different performances.3 This freedom (what Brian Cantwell Smith calls “flex and slop”) is necessary for representation to work.

Tantacrul sums this up efficiently as “the advantage of symbolism over literalism”, but here I wanted to dig into some of the details of why this works.

Back to the video

This is a good point to go back to “Notation Must Die” and see if any of this stuff I’ve been infodumping about is actually useful for thinking about it. I can see some connections but I’m figuring it out as I go.

A couple of the proposed reforms Tantacrul talks about move closer to the spectrogram end of representation. One idea that comes up repeatedly is to get rid of special notation for note lengths and instead use rectangles to represent notes, with rectangle length representing note duration, similar to the visualisation of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge in this video. This is a step closer to just using the time axis of the spectrogram. It’s a compelling idea to many reformers because it’s simple, and saves needing a load of special symbols, but it comes with some of the same locked-to-a-single-context problems of the spectrogram. You’re stuck with the physical length of the notes on the page being completely determined by their duration, which isn’t ideal when there is competing information on things like sharps and flats that also has to be represented somehow. Also, the rectangles sort of blend into each other, and are hard to tell apart for similar note lengths, whereas with discrete symbols there’s a big obvious change to look out for.

Another popular reform is to get rid of sharps and flats, which saves some of the “competing information” part of the rectangle problem, but introduces other problems. Normally this is done by introducing a “chromatic staff”, a staff with a line or space for every semitone, instead of modifying notes with symbols. (Here’s one explanation of the concept I found with some quick googling, not sure how great it is. Or watch this part of the video.)

This is a step closer to just using the frequency axis of the spectrogram. It’s still discretised, but in a more fine-grained way, and without the need for extra symbols. It’s not a bad idea exactly, but it does come with compromises of its own. It takes up more vertical space, and larger intervals like sixths and sevenths can be hard to read off instantly because of the sheer number of lines.

OK, so the spectrogram idea is somewhat useful for thinking about these two types of reforms, but I’m not sure how much it helps the rest of the video. There’s a section on tablature, another category of notational reform that gives up the flexibility of general music notation in order to make it simpler for a particular instrument. The most famous and popular is guitar tab, and there are also less successful attempts at piano tab. I haven’t thought very clearly about tablature yet. It’s another kind of locking to context, but this time the context of one instrument.

Tablature is more literal than normal notation, telling you exactly where to put your fingers for each note, but gives you fewer resources for understanding the music. Or, as Tantacrul puts it:

Pictograms are generally more immediately intuitive than symbols because symbols are abstract. You need to learn what they mean. But it’s precisely this abstraction that gives musical symbols so much power. Once you know what they mean and once your hands know where to go, they connect you much more directly to written to music and you can process it much faster. God this is turning into an undergrad semiotics essay.

So, maybe all this stuff is obvious and I should have just quoted this instead of subjecting you all to my undergrad semiotics essay? It’s certainly not been obvious for me, though, and I think this sort of analysis in terms of the middle distance does go deeper by probing into what “abstracting” actually means, and looking at the conditions of possibility for something to represent something else at all. Anyway, it’s been useful for me to think through some different examples to normal, even if the analysis is still a bit half-baked.

Other things

I wrote up a notebook post on single-character variable names in maths and programming, Variable names as handles or sigils. I intended to write more notebook posts this month but the second one got out of hand and turned into this newsletter.

Also, here’s the cover picture, which I took a few years ago. It’s a copy of Sumer is icumen in, written in mensural notation and displayed in the ruins of Reading Abbey, where it was first written down.

Next month

No particular plans, but that quote about undergrad semiotics essays makes me think, uhh, maybe I should actually read some semiotics? Given that it’s a field that’s claimed a bunch of territory near this notation area I seem to be fascinated with. So far I’ve just skimmed some intro material online and it looks like there are links to Saussure and Derrida and Wittgenstein but the core is more like, what, Barthes? Peirce? Jakobson? I don’t know these people at all, anyone got any suggestions on what I should read?

Hm, I said at the start that there wouldn’t be any physics this time. I guess that wasn’t completely true.

Derrida talks about this in Of Grammatology in terms of the difference between music and birdsong. More about this in my old braindump here, though I wrote that before I’d read much in this area and it might be full of wrong stuff, idk.

There’s some connection here between representation and digitality, which I don’t understand well, though probably these notes I made on Haugeland’s ideas about digitality are relevant.

You might be interested in the concept of 'basic-level categories' which would make a good companion to the 'middle distance' and would provide more examples. Well treated in Lakoff's 'Women, Fire and Dangerous Things' that also explores the consequences.

I thought the cat pictures would be like this: <https://xkcd.com/26/>.